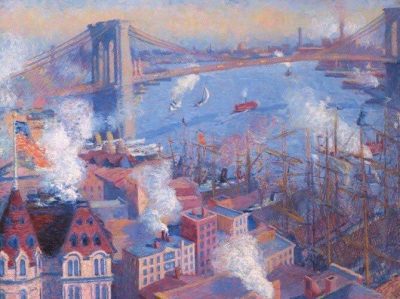

Losing homeland: Exploring Brooklyn’s Ukrainian connections

In a series of evocative photographs, Alina Patrick documents war-torn Ukraine and its reverberations 5,000 miles away in Brooklyn

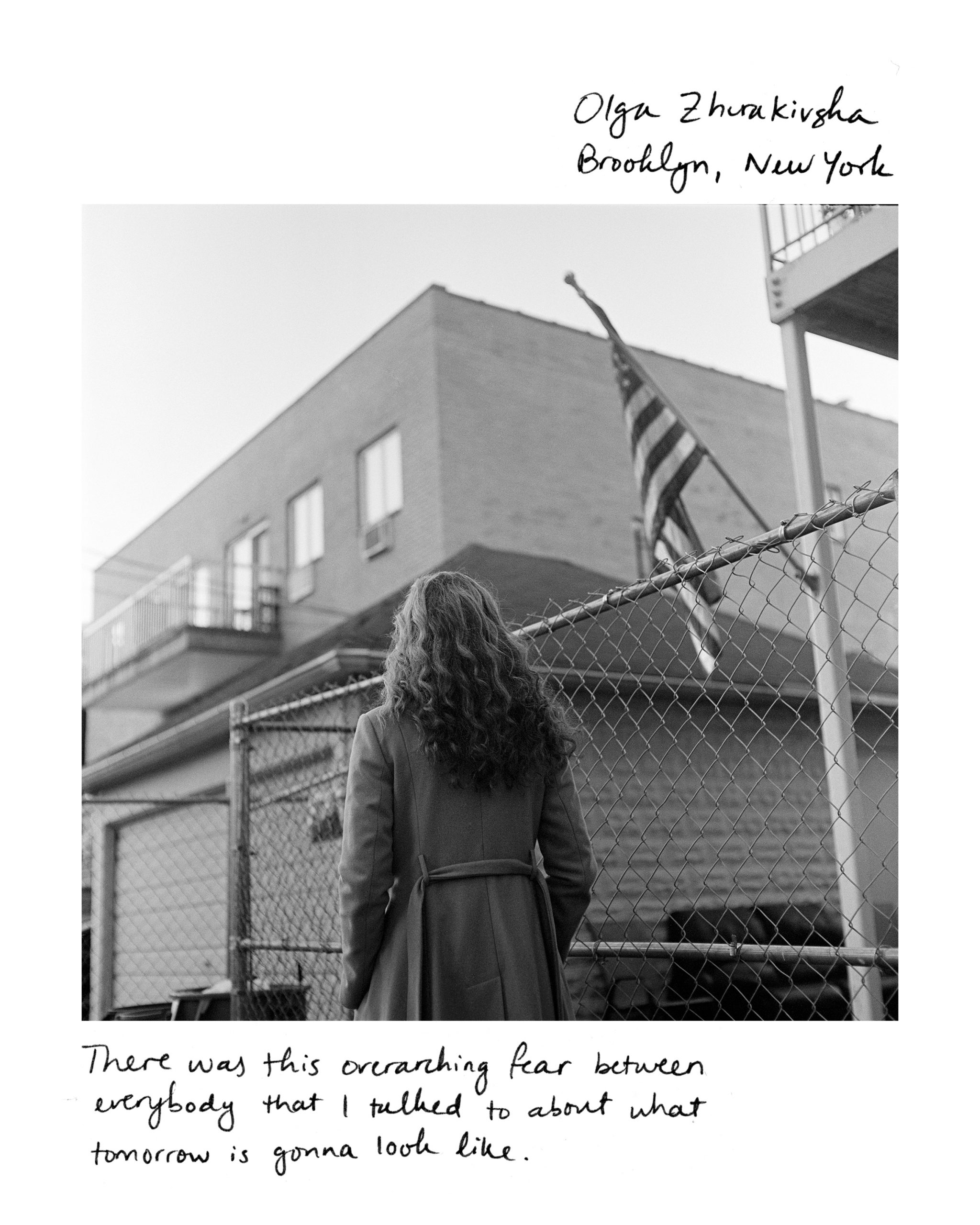

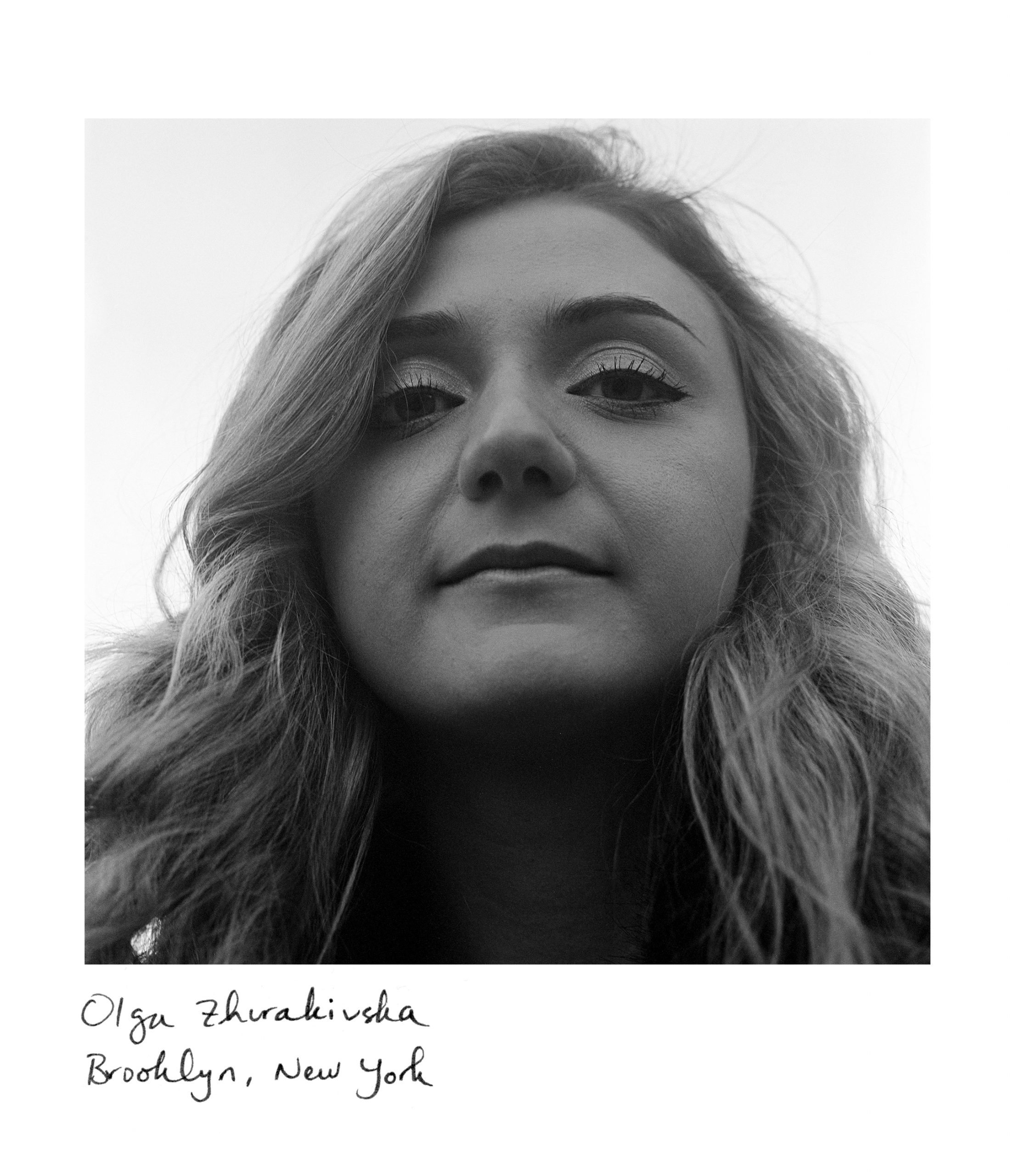

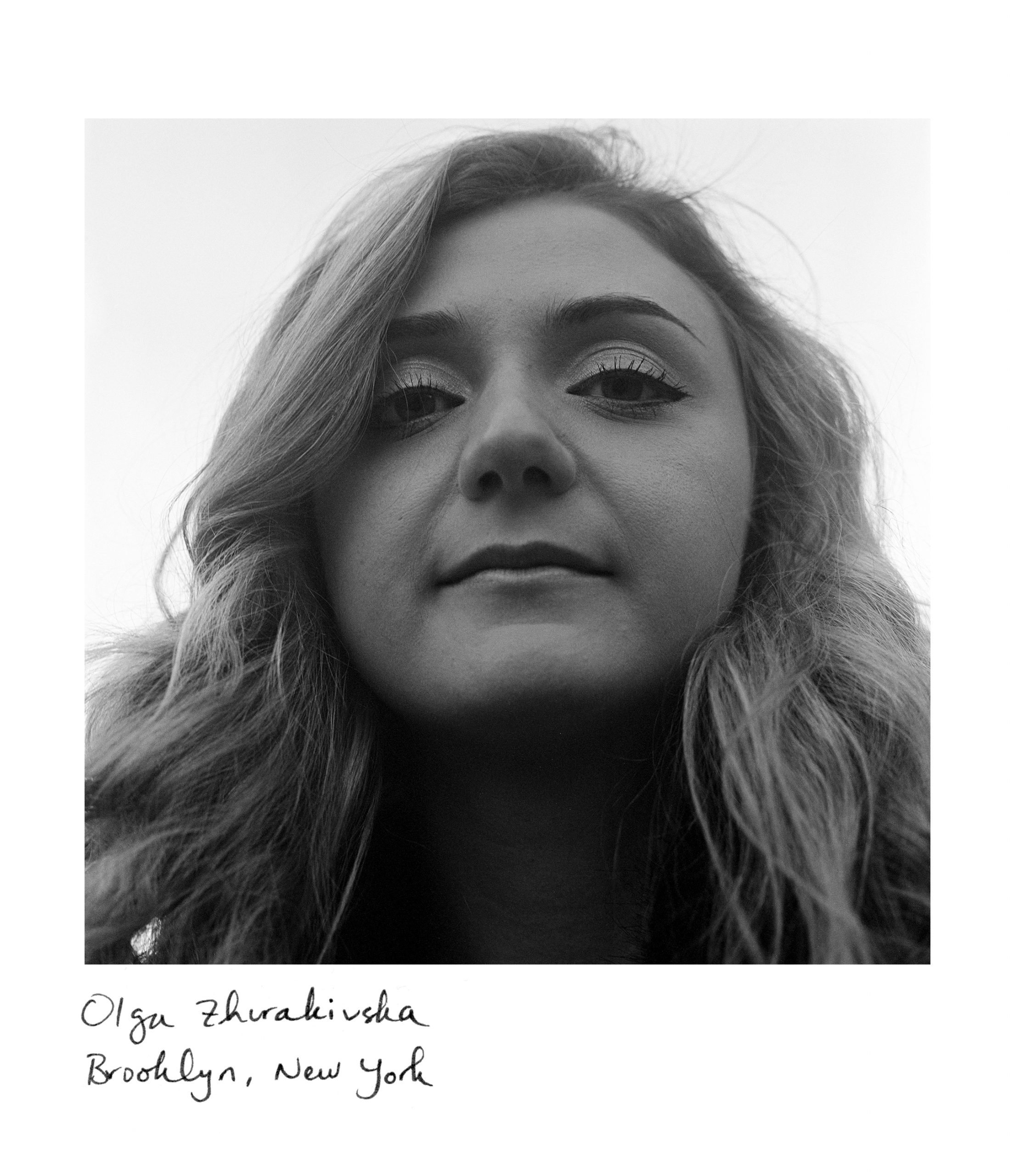

Most Americans probably can’t place Ukraine on a map. If many of them have heard about it at all, it was in 2019 when then-President Donald Trump tried to pressure Ukraine to investigate his political opponents and support conspiracy theories which would damage them. But for thousands of Brooklynites, Ukraine means so much more. For people like Olga Zhurakivska, it’s a homeland that is being chipped away at slowly as she watches from nearly 5,000 miles away.

In 2012, a teenage Zhurakivska moved to Brooklyn from Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine. She attended high school in New York, settled into her life in the city, and, like many Ukrainian-Americans, visited home when she could. The summer after she graduated high school, a visit that should have been full of celebration, was instead colored by palpable political tension. In only a few months, President Yanukovych would be ousted from power in the Maidan Revolution, triggering a harsh backlash from Russia.

“People were very, very scared,” says Zhurakivska.

Photo by Alina Patrick

The country survived the revolution. But then Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula, beginning what would lead to the Ukrainian-Russian war, still raging today in Donbas, an eastern region of Ukraine.

Back in Brooklyn now, Zhurakivska and her family continue to feel the shockwaves of the conflict, like so many others in the Ukrainian community here. Her own mother’s godson was killed in the war at just 21, newly married before leaving for eastern Ukraine.

She hears from relatives and families of school friends who worry about “whether or not their son is gonna get dragged out of their house in the middle of the night to go to the army and actually die,” she says. She also knows families in which the men have volunteered to join the army. “I just heard stories of how the wives literally fell on their knees to beg them not to leave because the death rate was so, so high.”

Photo by Alina Patrick

The Zhurakivska clan is just one of many Ukrainian families in Brooklyn—mostly concentrated in the Bensonhurst and Brighton Beach neighborhoods—and the greater New York area feeling the ongoing effects of the conflict in Ukraine. An astute observer will notice donation boxes to help fund foundations for internally displaced persons or the military inside churches and Ukrainian cultural centers, such as St. George Ukrainian Catholic Church in the East Village.

Photo by Alina Patrick

Daria, a volunteer at the Ukrainian kitchen Streecha in the East Village, comes every Friday morning to make varenyky (a Ukrainian dumpling) to sell at St. George. (Photo by Alina Patrick)

Across the ocean, in Kharkiv, a bustling industrial city in eastern Ukraine not totally unlike New York, nonprofit organizations such as Stansiya Kharkiv are also working hard to help some of the region’s 250,000-plus internally displaced people. Stanisya Kharkiv helps them find housing and healthcare, but limited resources and regional prejudices against those coming in (including fear-mongering about them stealing jobs), makes the transition difficult for many.

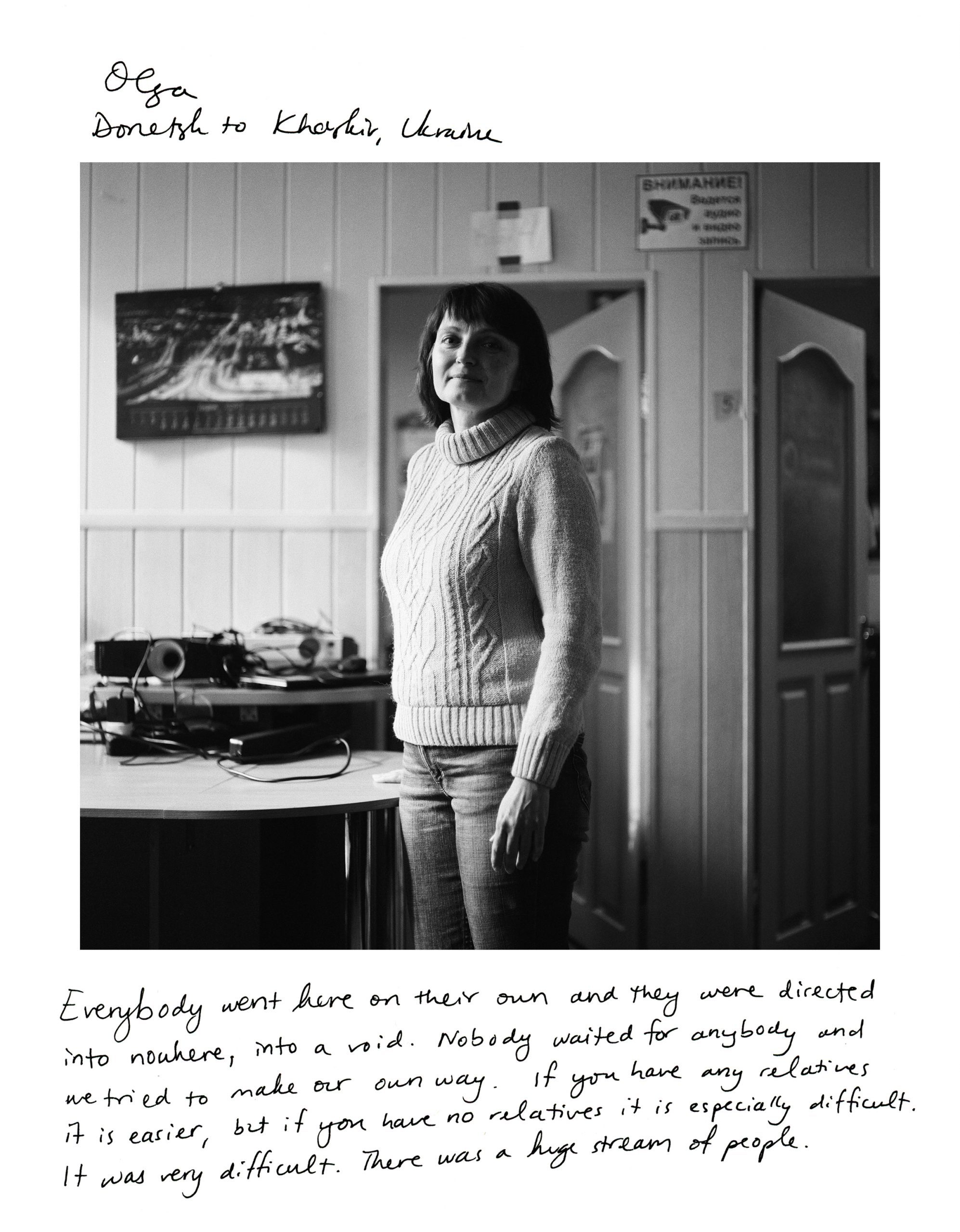

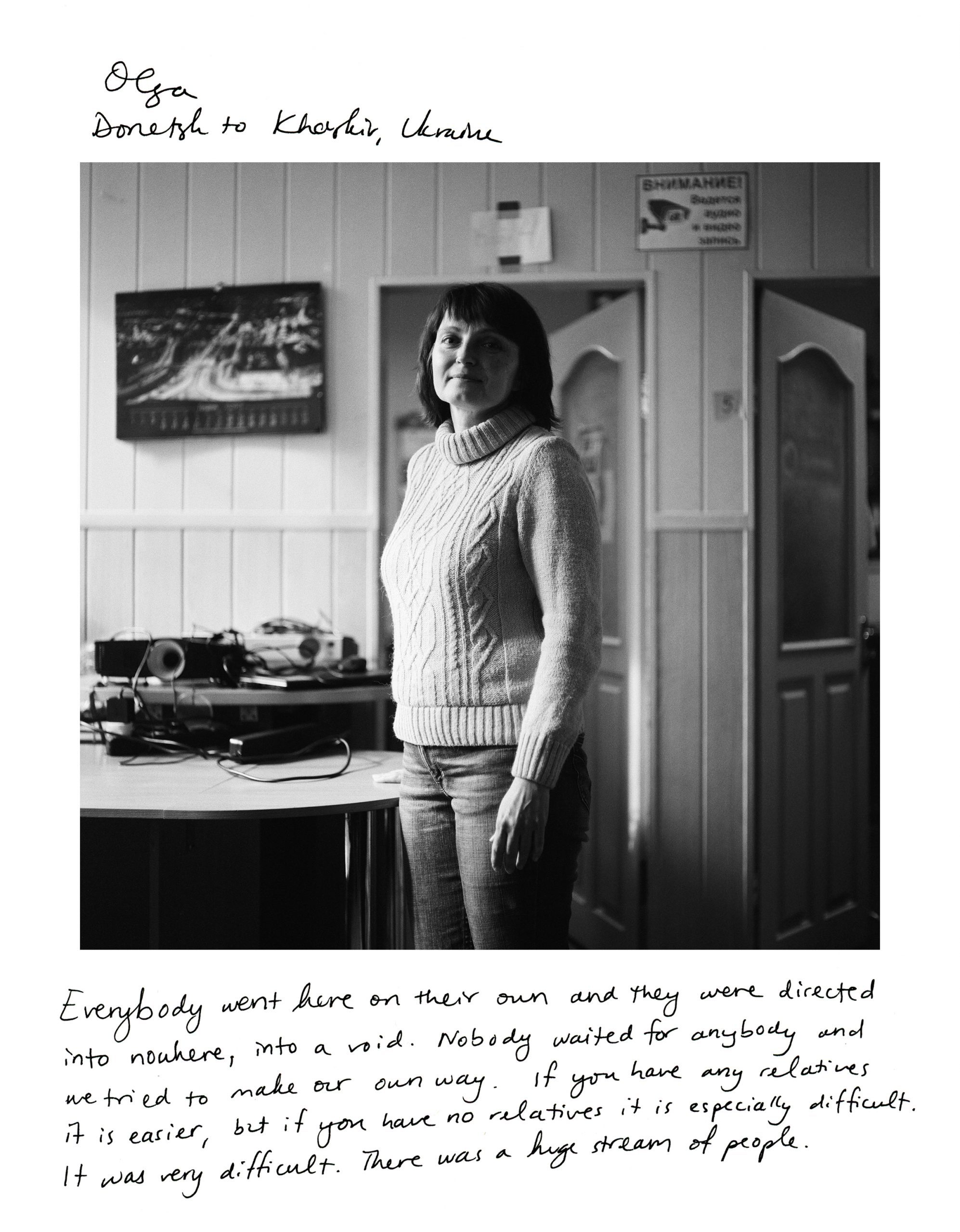

Olga at the Stansiya Kharkiv building in Kharkiv, Ukraine where she now volunteers. (Photo by Alina Patrick)

Another woman named Olga (who declined to give her last name name), fled Donbas, the region of Ukraine where the conflict is raging, in 2014 after the war with Russia began. Her daughter was planning to attend university in Donbas, but then tragedy struck: “War destroyed all our plans,” she says. “That’s why we came here.” Eventually, her daughter was able to earn a degree from a local university in Kharkiv. Although she misses her home immensely, Olga does not believe it will be possible to ever move back. Now, she volunteers at Stansiya Kharkiv to help other internally displaced people.

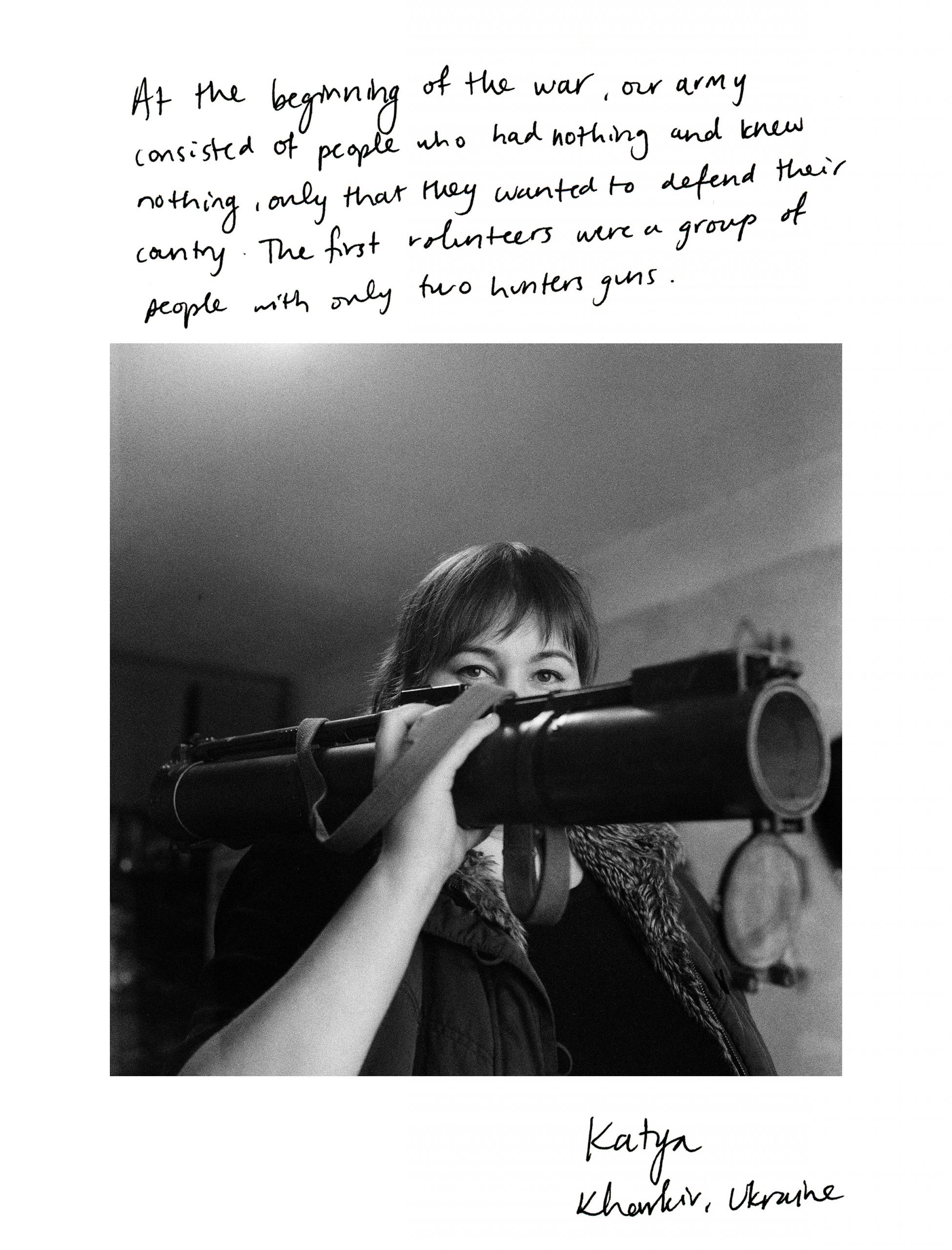

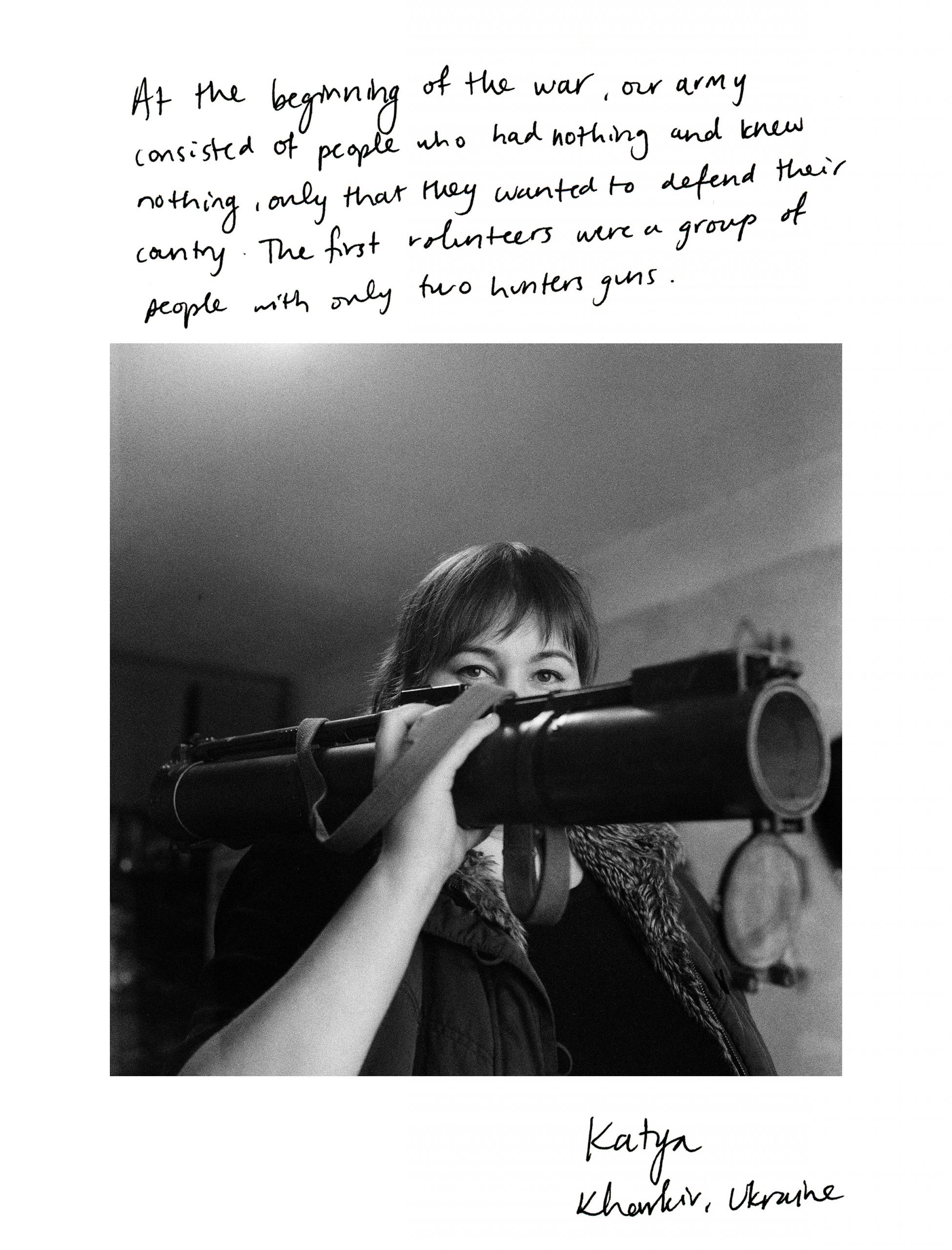

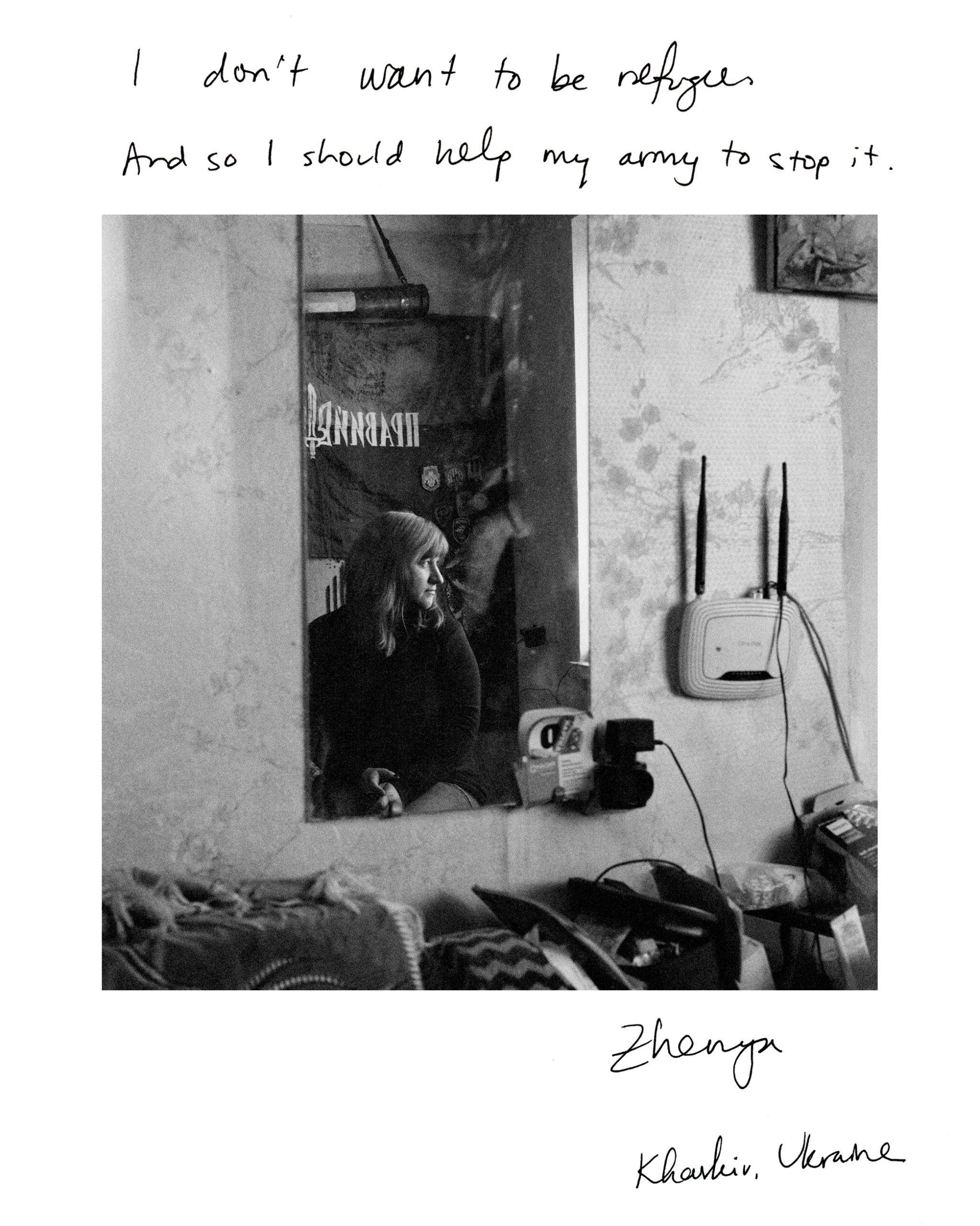

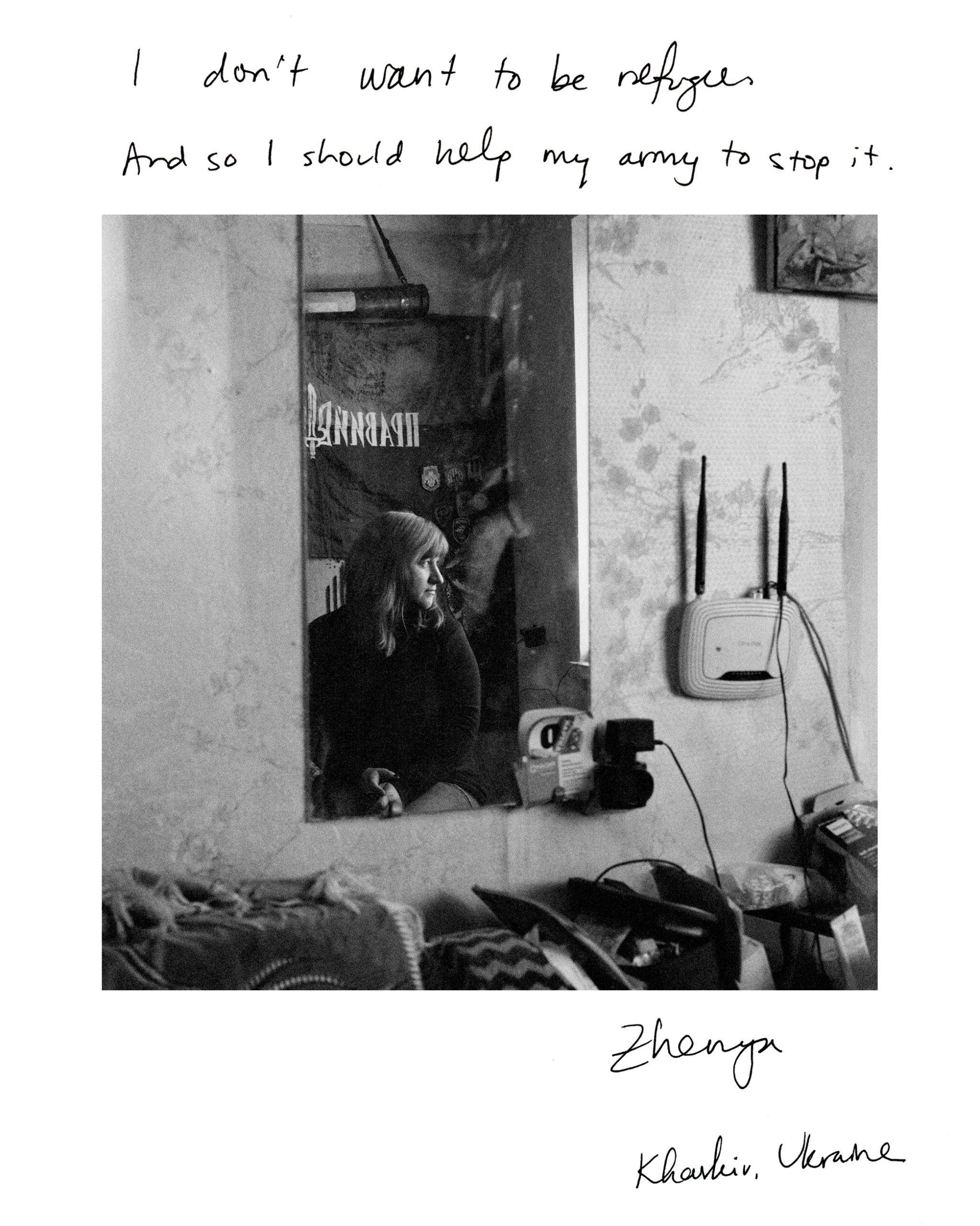

Olga is hardly the only Ukrainian volunteering to help those affected by the conflict. Many citizens participate directly not only as soldiers but also as volunteers at nonprofits and by fundraising for the military. Frustrated by the lack of resources available to the army, Zhenya and Katya, both based in Kharkiv, decided to take matters into their own hands by fundraising to buy jeeps, medicine, and car parts to bring to Donbas. Twice a month they pack up their cars and take the drive bringing these supplies to Donbas and then staying to volunteer as ambulance drivers.

Years after President Trump’s impeachment investigation, the media has all but forgotten that this conflict drags on. But for the displaced families in Kharkiv and those here in Brooklyn, it remains a horrifying daily reality.

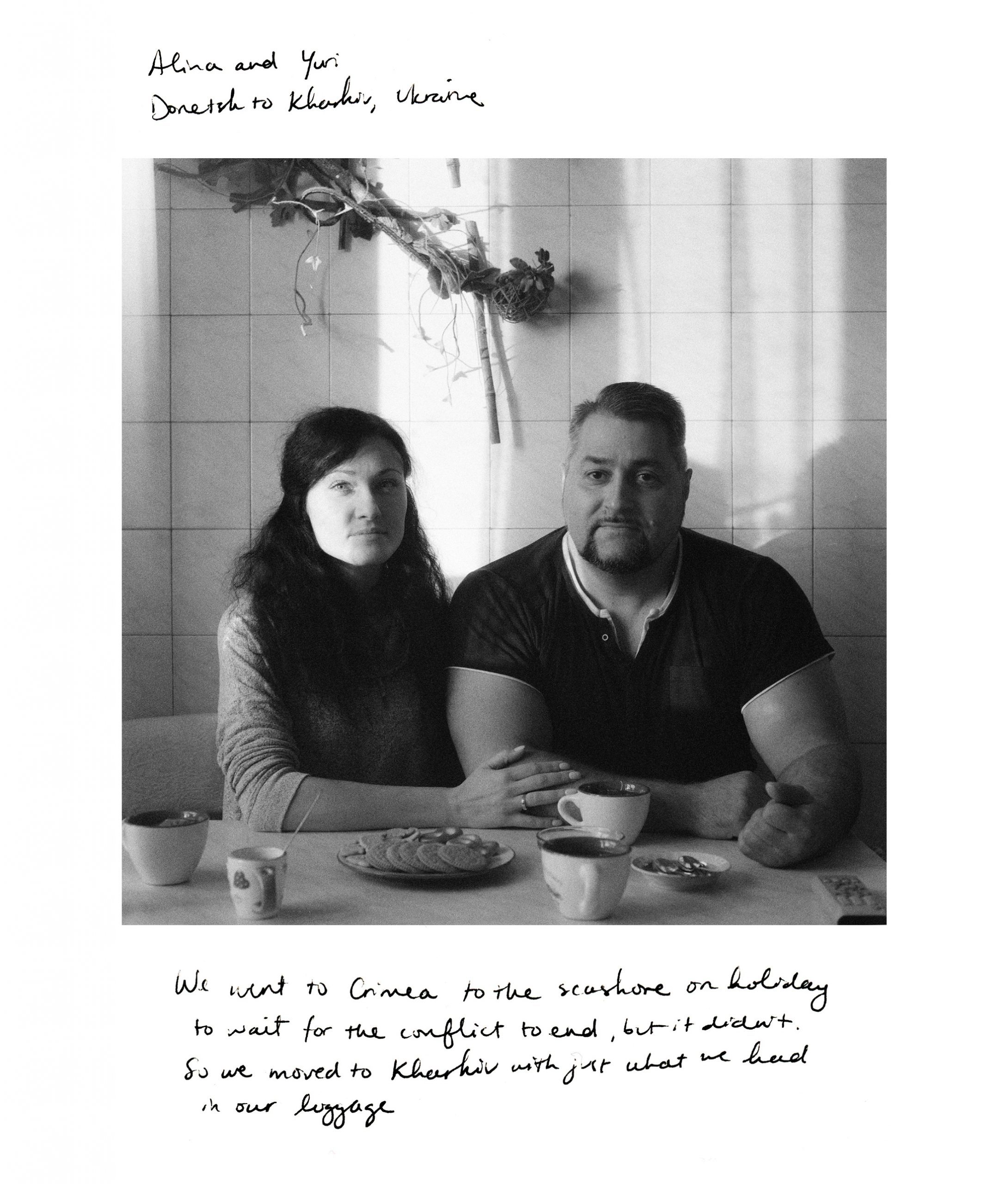

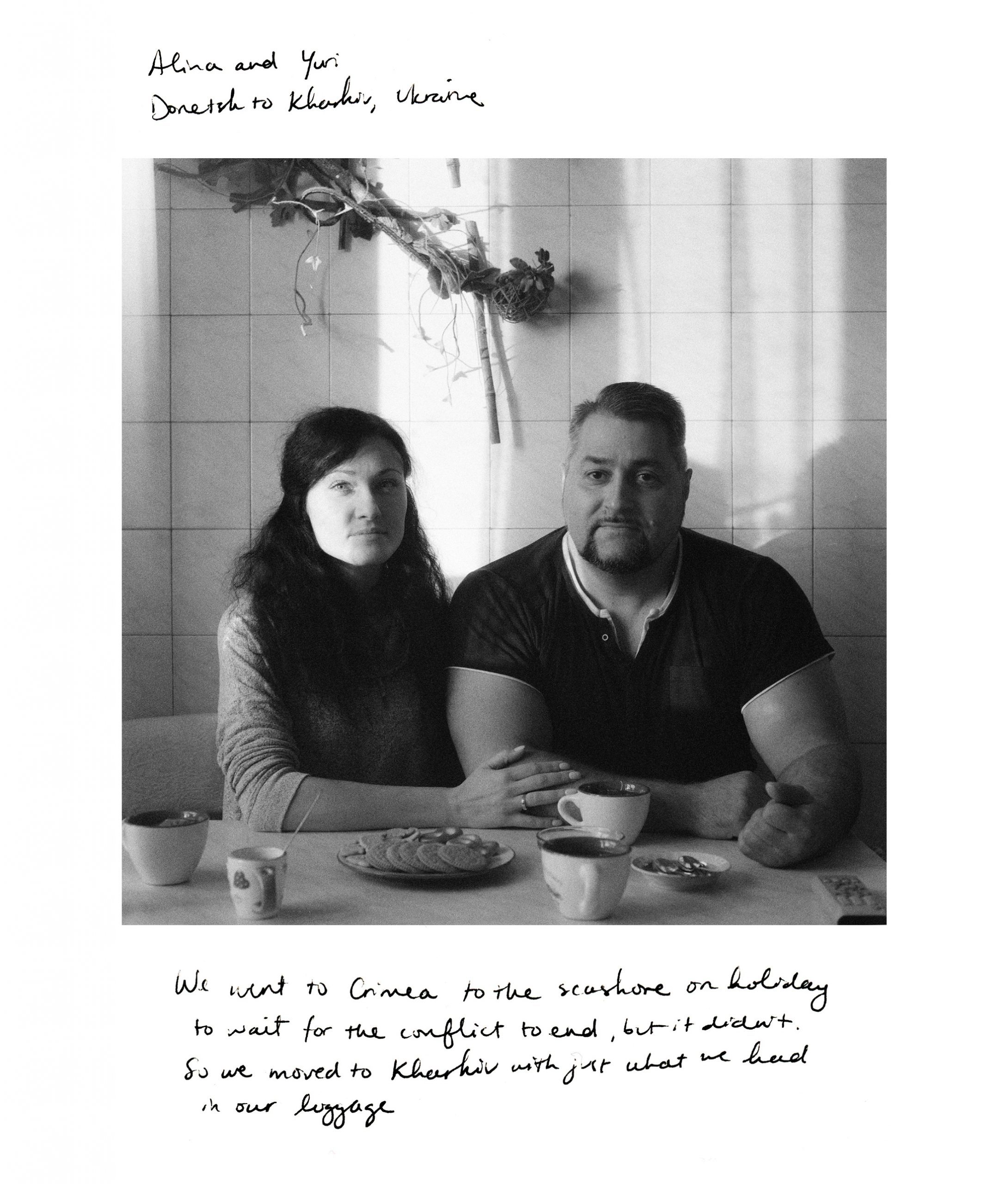

Two internally displaced people, Alina and Yuri, in their kitchen in Kharkiv where they relocated after leaving their home. (Photo by Alina Patrick)

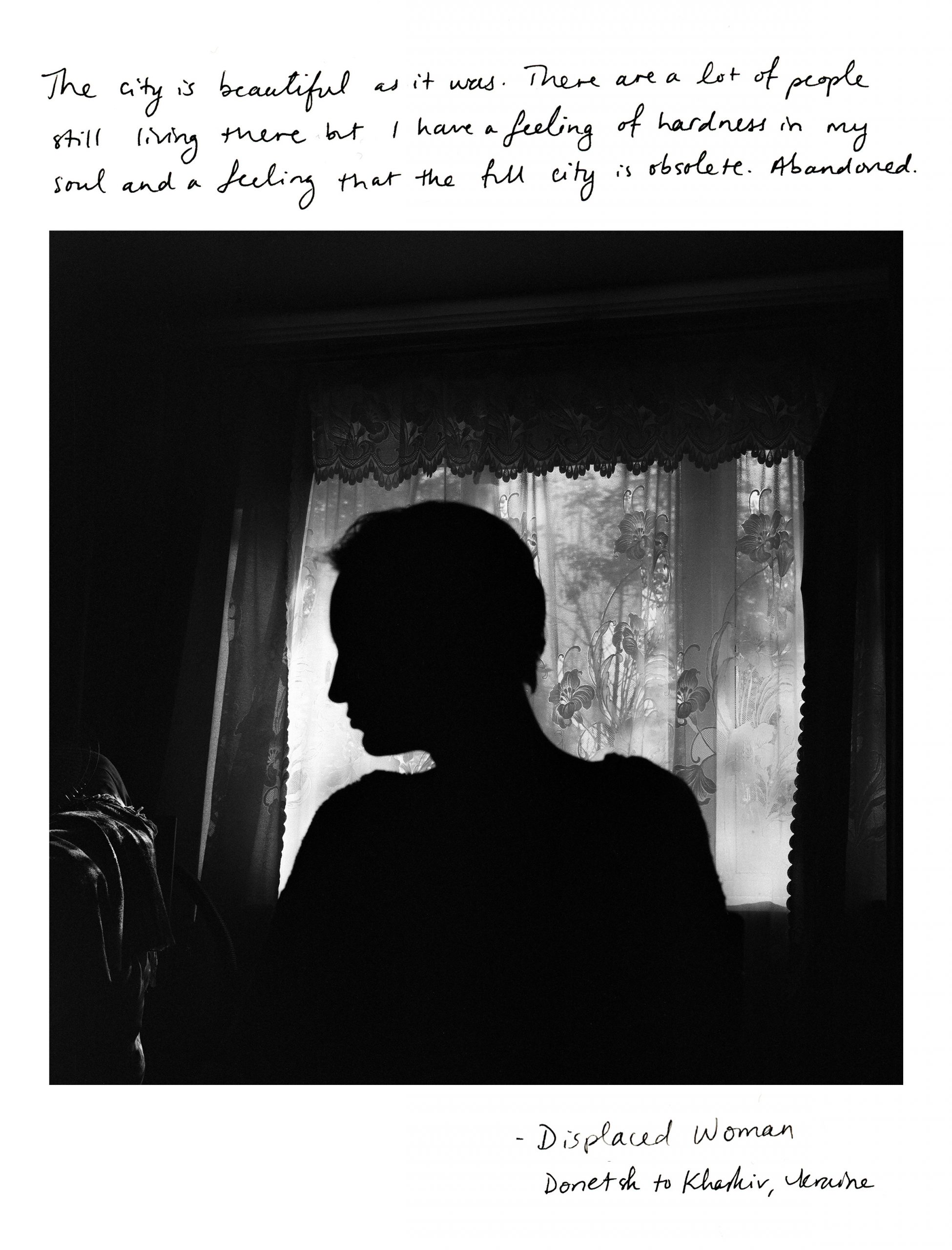

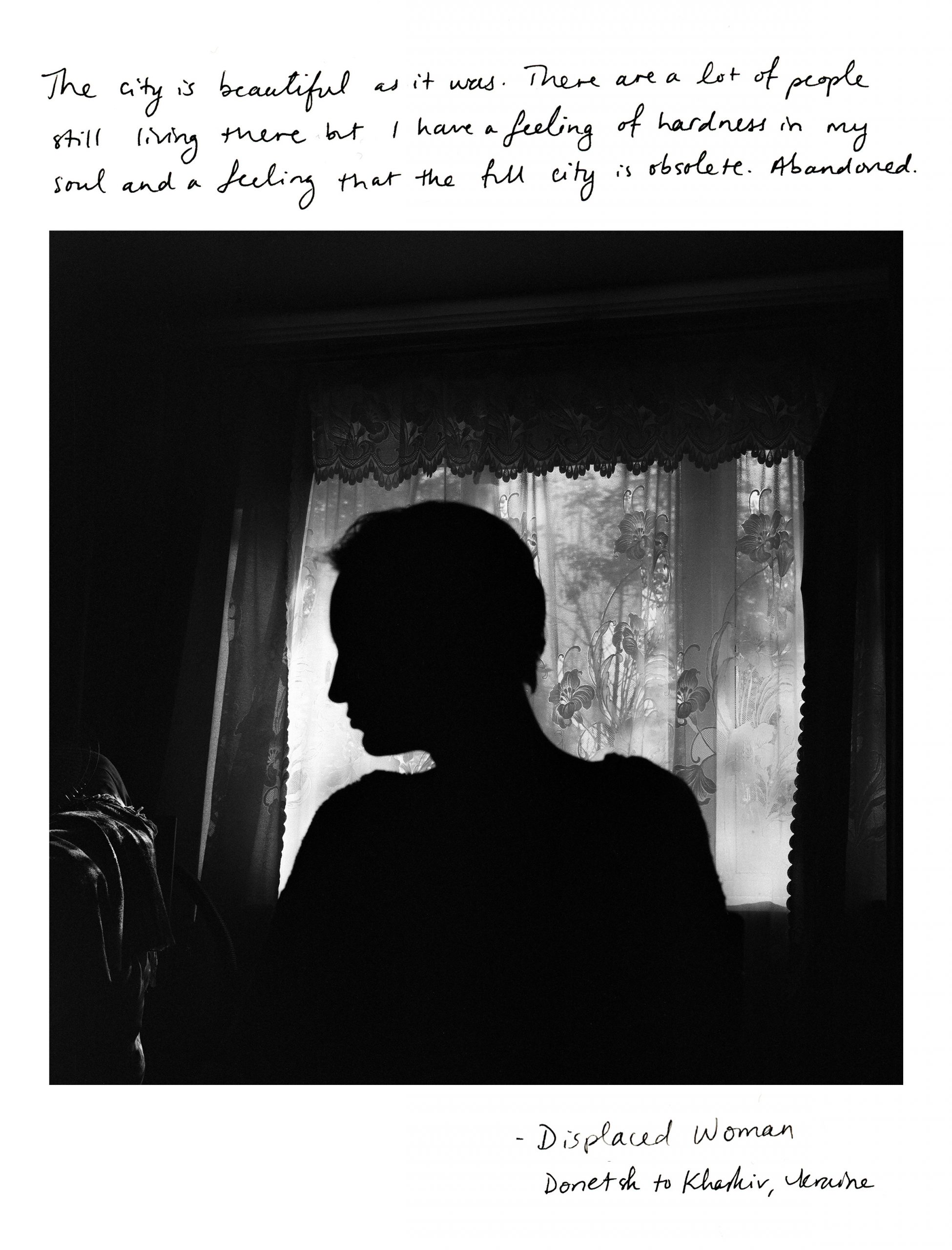

After being forced to give up her job as a social worker in Donetsk due to the constant violence, this woman—who preferred to go unnamed—moved to Kharkiv to work as a psychologist. She now provides veterans and internally displaced families with therapy through the Red Cross. (Photo by Alina Patrick)

Katya holds a broken grenade launcher she brought back from one of her trips to Donbas where she volunteers to help the military with car repairs and working as an ambulance driver. (Photo by Alina Patrick)

Zhenya volunteers for the Ukrainian military through fundraising over social media, driving ambulances, and repairing vehicles in Donbas. (Photo by Alina Patrick)

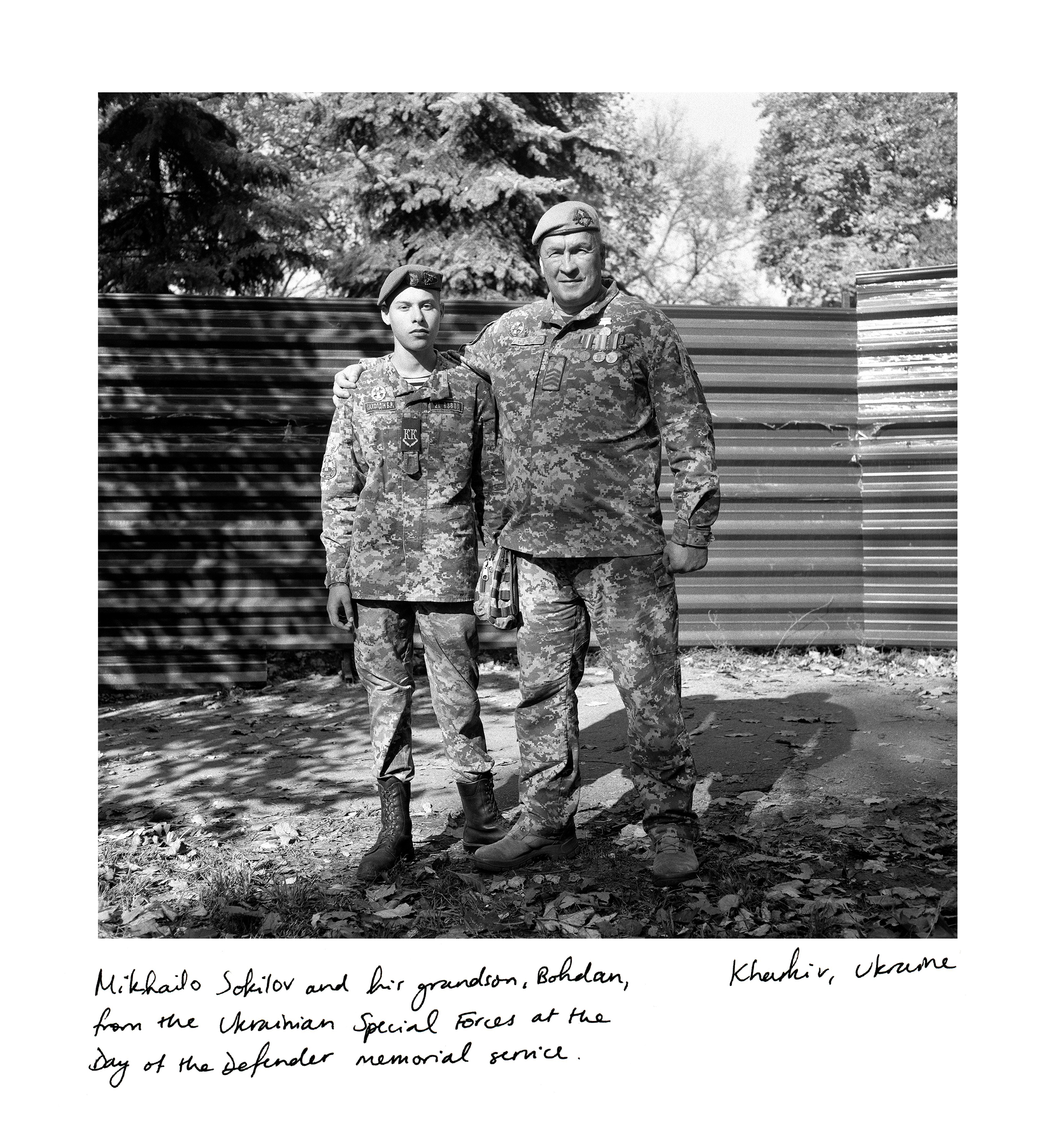

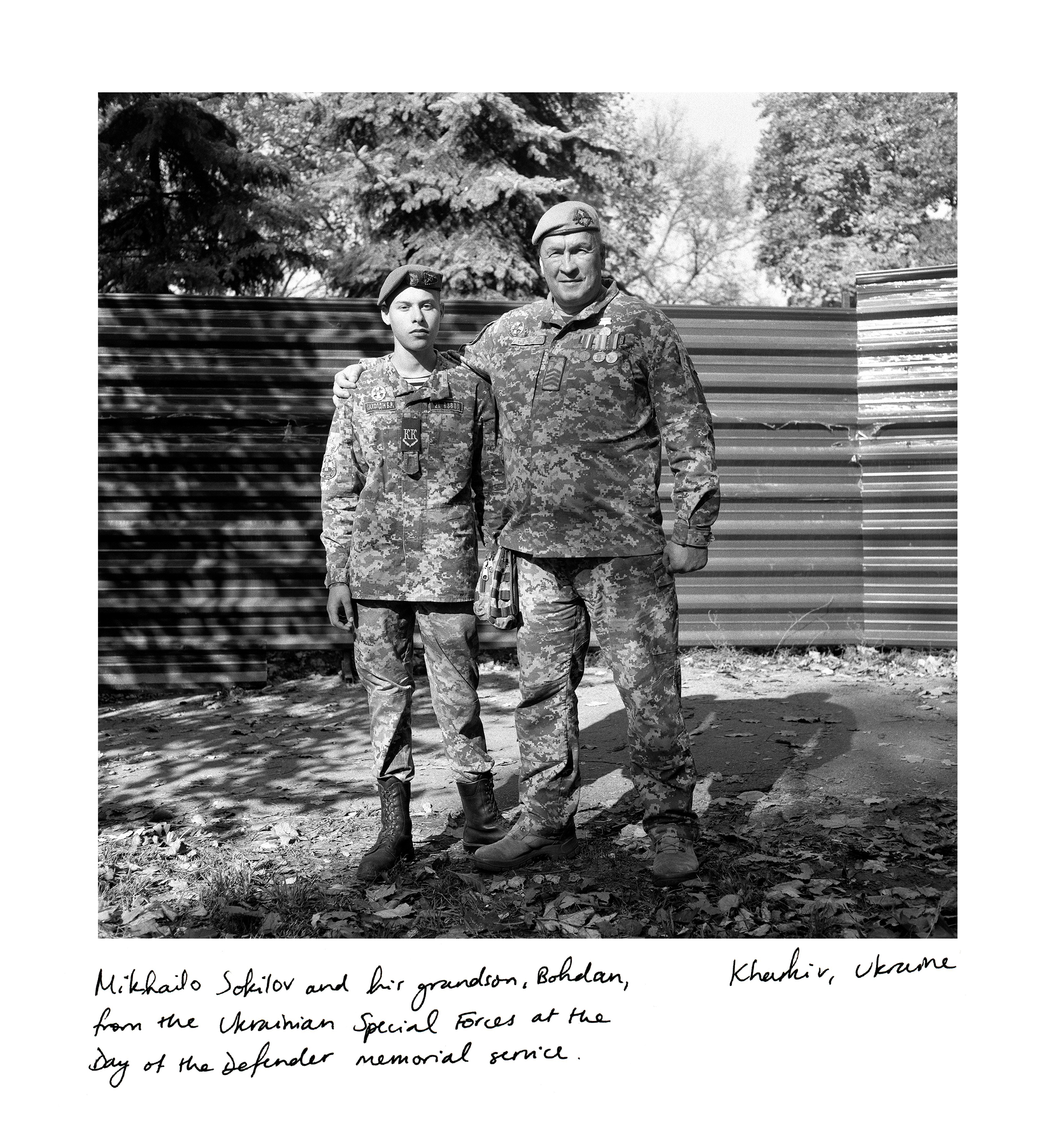

Sokilov and his grandson, Bohdan, stand together at the Ukrainian Day of the Defender memorial service in Kharkiv, Ukraine. (Photo by Alina Patrick)

You might also like