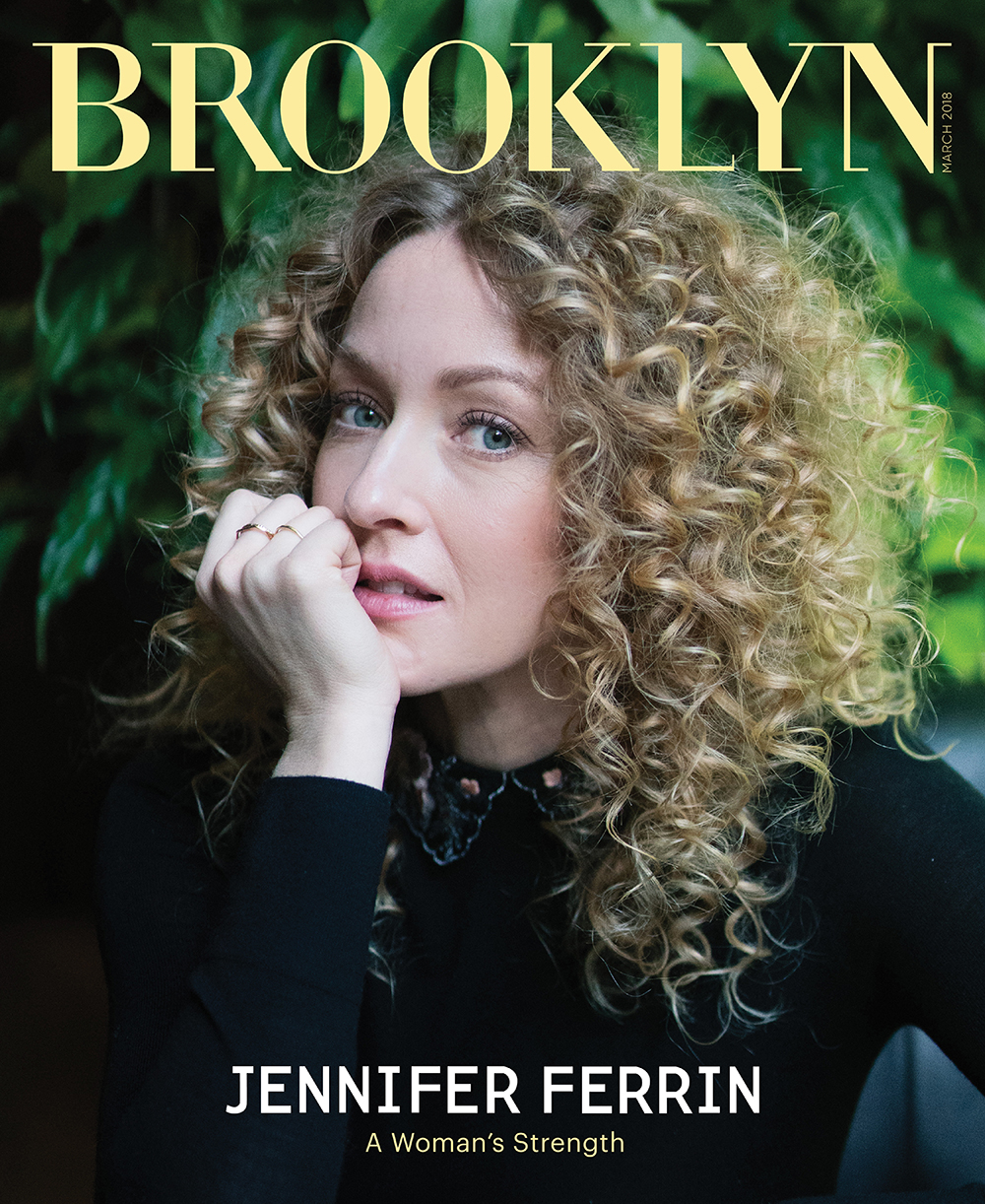

A Woman’s Strength: Jennifer Ferrin Talks Creative Freedom and Strong Female Characters

PHOTOGRAPHY Aubrey Wipfli

In Mosaic, HBO’S six episode television series directed by Steven Soderbergh, Jennifer Ferrin plays Petra Neill, the calculating sister of a man accused of murdering the famous artist, Olivia Lake, played by Sharon Stone, in Summit, Colorado. Though she’d been estranged from her brother—a seasoned con-artist—Petra is convinced that he’s innocent and sets aside her art career in Denver to launch an independent one-woman investigation into the murder. In her role as Petra, Jennifer is precise and dogged in search of justice.

From the stony reserve of Petra Neill (Mosaic), a reporter in the hyper-masculine wild west (Hell On Wheels), to a patient that loses her nose to syphilis in a turn-of-the-century New York medical drama (The Knick), Jennifer’s performances seem to center strong women characters who, regardless of time and place, live on the fringes of society. But what exactly did that strength, and how I understood it, mean?

When we turn real people’s lives into symbols, those lives, and what they mean to the people who live them cease to matter as much as what we want them to. By romanticizing the idea of strength and what it looks like, I realized that I was making symbols of the women Jennifer was worked to dimensionalize, so that we’re seen as more than a categorical definition.

Heading to meet Jennifer at Café Devocion, in Williamsburg, on the B44, I thought about how my own want for symbols had sometimes even kept me from seeing this. Arriving in a finely pleated skirt and cashmere sweater with a beaded collar, Jennifer beamed with a freedom that couldn’t be bought. Over the course of our two hour conversation in that Grand Street café, we talked about that freedom in the context of how she picks her roles, and why the ability to choose matters.

How do you define “strong” women?

I dare to say that EVERY woman is a strong woman. Just by the nature of how we are made, what we have to endure by what society, our families, and careers ask of us. I am constantly in awe of the women in my life who juggle the roles of mother, wife, breadwinner, caretaker, business owner, sister, daughter, friend, and human, and manage to stay resilient through the ups and downs.

What are you looking for, then, in the roles you choose?

When the writers and creatives surrounding the project have a real vision, that’s key. Working with Steven Soderbergh, I’ve been spoiled. He is most interested in telling a story that makes the audience participate. It’s what he requires, having creative freedom. So, to work with him, to play within that sandbox is a dream.

You have said that working with Soderbergh made you a better actor because you have to trust your choices. As an actor, what does trust and choice mean?

That’s a really good question. I think trust exists on two levels. There’s trusting the people you’re working with and there’s trusting yourself. Steven works very fast. He doesn’t do rehearsals. He doesn’t do a lot of takes. While he’s very much in control of his playground, he doesn’t have a lot interest in putting his fingerprints on your work. When he hires you as an actor, he pretty much leaves you alone. He goes, “Okay, I know what this person can do.” He’s trusting you.

Whenever I’m having doubts about something, I go back to the work. I go back to the page, and ask, “What am I doing here? What are the choices I can make around this?” That sort of trust allows you to say, “I have to trust myself.” It’s not always easy.

Where does choice come from as an actor? Is it instinctual or something you have to develop over time?

Having a good script is everything because that’s your road map. For my character in “Mosaic,” I started with her name, Petra. I said, “Okay, what does that mean to me?” Petra in Greek means stone. Something very hard and cold. From there, I saw her character as dark. Guarded.

In the script, [Petra] talks about keeping emotions at bay. The way she deals with her family, and the things that have happened. Those were clues. I think that’s where choice comes from: allowing the curiosity about a character lead you toward these clues that help you gure out who you’re playing. For me, it’s helpful when it comes from a physical place. The kind of clothes that she wears. Everything that you put on this morning is connected to something, and some part of your personality.

Does costuming really help evolve a character?

Absolutely. Shoes, too. There are times when I’ll be rehearsing in more of a traditional television show. Oftentimes, they’re like, “Do you want to rehearse in your shoes?” And I say yes because it informs how I’m moving.

[On “Mosaic”] we had incredible costumes done by Susan Lyall. It’s like, “Okay, this character [Petra] is an artist. She’s not a New York City artist. She’s in Denver. She is trying to divorce herself from her childhood. She’s not anything like her brother. What does that look like?” Petra also hides. Everything she wears is very layered and square. She’s not showing her figure at all. [Susan and I] worked together on how to show that through what Petra wears.

What’s the common thread between the characters you’ve played? How have your roles evolved?

There is often an elegance and will to the women I’ve played. A clear sense of purpose and determination. I think probably because I carry those qualities myself. But as my career has evolved, it’s been so rewarding to find the deeper layers to those women—the cracks and vulnerable bits we all have that make us more human. It’s why I’ve enjoyed playing characters from different time periods when social graces forced them to put on a particular face. But behind closed doors you get to see their true nature. I love seeing how people behave when they think no one’s watching.

What have your biggest challenges been as an actor?

I think the biggest one is believing that what I do matters. It goes back to what I was saying before about the trajectory of an actor’s career. In the beginning, you just want to get work. The roles don’t always align, and the story you’re telling doesn’t always feel like it needs to be told, but you need the paycheck.

I’ve worked for 15 years. I’m so incredibly lucky, but there are times where you don’t get to choose. You just are so grateful for the next job. You’re grateful for the paycheck, and you hope that one will build upon the other. I just wanted to make my living as an actor, doing what I love to do. Now I have the opportunity to, potentially, direct this a bit more. Instead of playing the guest star on every single New York show, which I’ve been so lucky to do, there’s an ability to ask myself, what kind of roles do I really want to be playing? That’s a big perk of having success.

Some would say it’s a responsibility. Or there’s these opposing ideas, right? On one hand there’s this idea that art is this pure thing that shouldn’t be beholden to politics; that you should be able to write whatever you want, produce whatever you want, etc. On the other hand and, as you said, with this increasingly successful platforms, there comes a responsibility.

I think we have to be present and have to participate in the world around us when we are make art. If not, we are doing a disservice to our community. Like you said, there is, a responsibility to do that. When we ignore [the responsibility] there’s an absence of truth that makes the work hollow.

Can you say more about that—the absence of truth?

You mentioned the idea of the purity of art. I don’t even know what that is. Maybe it’s because I’m an actress, so I am constantly affected by the world around me. I’m affected by my fellow actors, the script, the weather, and I’m a woman. I just think that you have the news that reports what’s going on in our world; but you have art to reflect our souls.

I think when you are able to take a political situation, a social situation, and you reflect it in an art form, you are able to touch more people as well, and affect more people in that way. That’s what brings about conversations that are less volatile.

If you get into the story of it, people let their defenses down a little bit more, and they can absorb the humanness. The truth of it, like you said.

It’s multi-layered—sometimes you just need an escape. We all need escape. Other times, for someone to see themselves, and their situation reflected allows them to have hope that they’re not alone. That their world is just as important as the worlds that are highlighted in our culture.

I’m interested in the process of storytelling. I’m interested in how the character reflects what I want to be putting out into the world. I’m really excited now to be able to have, hopefully, the opportunity to choose stories that matter more, characters that are representing people that need to be represented. There’s a lot of joy to be had, and I think now’s the time. There’s a lot to reflect with the women’s movement and equality. I don’t know what the story is necessarily is going to be, but my receptors are much more open now to the importance of that.

You might also like